I’m attending the Algorithms 1 course on Coursera, from professors Robert Sedgewick and Kevin Wayne, and so far it’s been great. It’s nice to remember and improve my knowledge in algorithms while coding solutions to unusual problems like the 8-puzzle problem (solved using the A* algorithm), and all of that for free! :-) This post is inspired on one of the applications of priorities queues: event driven simulations.

After studying sorting algorithms (selection, insertion, shell, merge, quick and heap sort) we were briefly exposed to collision simulation and its naïve O(n^2) and improved O(n lg N) solutions.

Since the improved solution is SO MUCH better in theory, I decided to try it myself, implementing both solutions with JavaScript on a HTML5 Canvas, a technology that I always wanted to use but had never found an opportunity.

Both implementations use the same structure of initialization/resource/drawing/warmup but they differ mostly on its update mechanism: the function responsible for calculating collisions between circles and walls and then moving them based on its direction and speed.

The simplistic approach uses a O(n^2) loop to check for collisions between every single particle since every one of them is a candidate to be at the same place at the same time, and only after that the postioning is calculated.

The event driven approach has a very different nature: its strategy is to predict collisions, keeping them in order and executing them one by one. This approach is powered by a priority queue that has both insert and remove operations with O(lg N) time.

Even having these solutions written in other languages and platforms they weren’t easy to implement, mainly because of the language. Don’t get me wrong: JavaScript is a great language, but it has so many “gotchas” that it took me a week of “freetime coding” to accomplish a bug-free solution.

People tend to praise JavaScript and even put down who criticize its problems, but I personally think that this is a childish behavior. I acknowledge JavaScript importance and I know that is possible to achieve great things with it, but no one can say that it isn’t unnecessarily hard to write complex systems with it.

Just by reading my code now I remembered five topics that it can be tricky:

- Equality (==) and strict equality (===) operators: http://stackoverflow.com/questions/359494/javascript-vs-does-it-matter-which-equal-operator-i-use

- Function Scoping: http://stackoverflow.com/questions/2295281/javascript-function-scope

- Absence of integer type: you can’t rely on integer divisions :(

- Optional parameters: there’s no support for that and if you misguidedly do an if(parameter) bad things may happen because values like 0 evaluate to false.

- Inheritance: this is a big and complex topic. There isn’t any classical (from classes) inheritance in JavaScript, so you need some plumbing code to simulate the behavior that is normally expected. I used in my code a simple prototypal inheritance (http://javascript.crockford.com/prototypal.html), a lot different from what people expect in inheritance. I’m thinking about writing another blog post on this subject in the future to help “pinning” inheritance patterns in my head.

So, let’s go to the code. It can be found in this repository: https://github.com/victorarias/collision_system

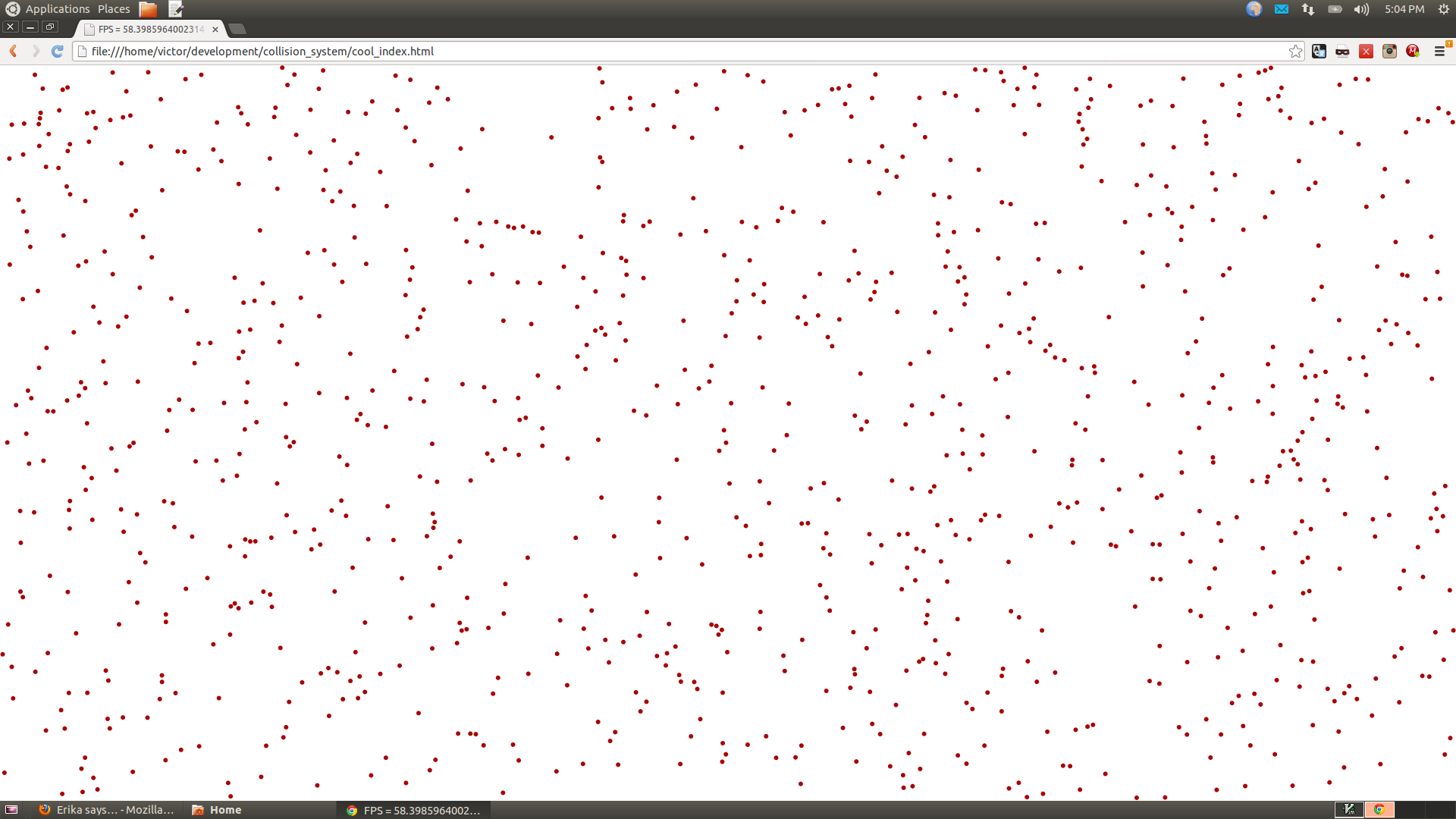

Below is a picture of the running code and a link to the demo:

The main files are listed below:

- priority_queue.js: data structure that enables the cool solution.

- circle.js: type to represent a circle on the canvas.

- collision_system.js: base type to run startup code and the main update+drawing code.

- simple_collision_system.js: O(n^2) implementation

- cool_collision_system.js: O(n lg n) implementation

- profiler.js: type to “hijack” functions and measure performance (just a simple arithmetic average)

Let’s take a look at the commented implementation of both implementations:

function SimpleCollisionSystem() {

this.update = function update() {

for(var a = 0; a < this.circles.length; a++) {

var circle1 = this.circles[a];

//n * n/2 loop to check for collisions on every other particle

for(var b = a + 1; b < this.circles.length; b++) {

var circle2 = this.circles[b];

circle1.checkCollisionOnAnotherCircle(circle2);

}

circle1.move(); //"walk" the particle

//check for collisions on the canvas border

circle1.checkCollisionOnX(this.canvas.width);

circle1.checkCollisionOnY(this.canvas.height);

}

}

}function CoolCollisionSystem() {

this.currentTime = 0;

this.pq = new PriorityQueue(eventComparator);

//warmup happens only at startup (duh), to predict collisions between every particle

//this is the only n^2 loop

this.warmUp = function() {

for(var i = 0, length = this.circles.length; i < length; i++) {

this.predict(this.circles[i]);

}

this.redraw();

};

//predict future collisions and insert then inside the priority queue

this.predict = function(circle) {

if(!circle) return;

for(var i = 0, length = this.circles.length; i < length; i++) {

var circleToHit = this.circles[i];

var dt = circle.timeToHit(circleToHit);

//the if below is an optimization to avoid distant predictions that will probably never happen

if(dt > 0 && dt < this.circles.length/2)

this.pq.enqueue(new Event(this.currentTime + dt, circle, circleToHit));

}

var dtX = circle.timeToHitVerticalWall(this.canvas.width);

var dtY = circle.timeToHitHorizontalWall(this.canvas.height);

this.pq.enqueue(new Event(this.currentTime + dtX, circle, null));

this.pq.enqueue(new Event(this.currentTime + dtY, null, circle));

};

//"hack" to keep the drawing away of the main loop

//this is necessary because drawing is also an event like a collision

this.oldDraw = this.draw;

this.draw = function(){};

this.redraw = function() {

this.oldDraw();

this.pq.enqueue(new Event(this.currentTime + .1, null, null));

};

this.update = function() {

//first we must find a valid event

var e = this.pq.dequeue();

while(!e.isValid())

e = this.pq.dequeue();

var a = e.circleA;

var b = e.circleB;

//"move" every particle to the moment of the selected event

for(var i = 0, length = this.circles.length; i < length; i++) {

this.circles[i].move(e.time - this.currentTime, this.canvas.width, this.canvas.height);

}

this.currentTime = e.time;

//do the collision or just redraw

if(a && b) a.bounceOff(b);

else if(a && !b) a.bounceOffVerticalWall();

else if(!a && b) b.bounceOffHorizontalWall();

else { this.redraw(); }

//predict new collisions with the event particles (if any)

this.predict(a);

this.predict(b);

};

}These implementations have very different performance considerations. Let’s look first at some raw numbers:

- Number of particles: 1000

- Simple 0(n^2) implementation: ~25 FPS

- Cool O(n lg n) implementation: ~58 FPS

These aren’t impressive numbers, right? On my machine 1000 particles is the point that the simplistic solution is at its limit: the browser can’t hold the animation above this. This is expected on the simplistic solution, however I expected a different result from the cool solution – at least this was what I thought when I first saw the numbers.

After some study I realized why this happened:

-

The cool solution is constrained not by the number of particles but instead by the number of collisions (so a change of radius will change the measured number).

-

The cool solution aim to a smooth simulation and not only to an animation, paying with “animation speed” instead of “animation quality”, meaning that the particles will decrease its velocity instead of start jumping on the screen.

The result is that the cool solution can actually handle much more particles in the simulation, but it will slow down the particles speed on big loads. Tweaks can be made to increase the speed on these scenarios (decreasing/increasing drawing rate, limiting even more the size of the priority queue, etc.), but these tweaks may not play well at common scenarios.

Coding these algorithms was a fun and very rewarding job. I’m a fan of deliberate practice as a technique of skill improving and this was a perfect example of it: a well-defined task, challenging but doable with easy feedback and a lot of opportunity to correct errors.

I must thank Coursera for the opportunity of taking these classes for free. Sincerely, I would pay for this kind of knowledge and exposure. I’m anxious to complete this course and start its second part!